Neck Rings in African Ornamental Culture

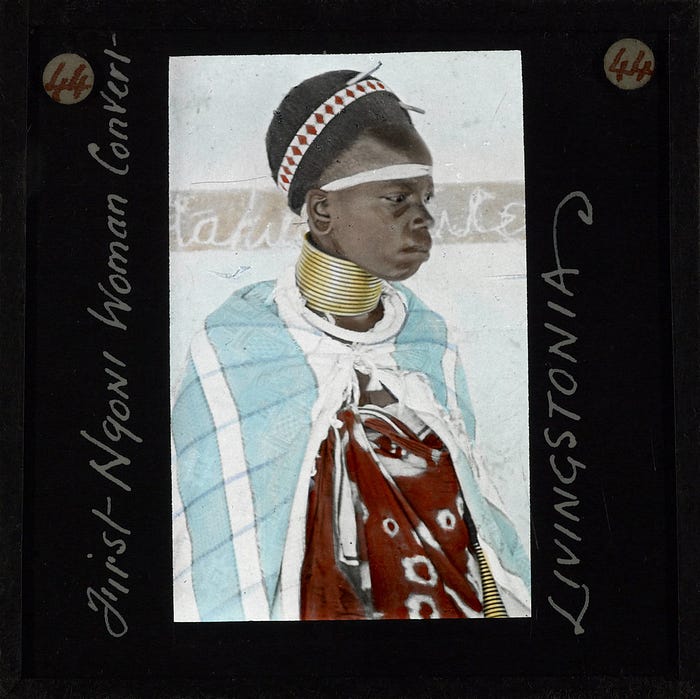

Except among the peoples for whom neck rings are still an important part of traditional or ceremonial garb, neck rings are no longer a common sight across the African continent. This is a different picture than a mere century ago when neck rings and collars made of copper, brass, bronze, iron, coral, clay, beads, and other materials were a popular accessory among various African peoples. Copper and its alloys (bronze and brass) were the most commonly used materials for neck rings. Copper was a highly valued metal, even more so than gold in some parts of the continent. Copper was used as a medium of exchange, in personal adornment, as an emblems of status and kingship, and to make cult objects. Copper, tin and zinc were mined locally or imported as bars, manillas, rings, wires, bells and basins. They were then melted, mixed, hammered, drawn, twisted or otherwise transformed into various objects. This versatility, the metal’s reddish color which linked it to notions of life, fertility, and transition, and its ability to be polished to a bright sheen also contributed to copper’s high value.

The Teke, found around Pool Malebo or Lake Nkunda in the Democratic Republic of Congo, were skilled metal workers and known for their flat brass neck rings. Teke kings and chiefs, as well as their wives, daughters, and other women over whom they had authority were known to wear large neck rings made of copper and its alloys. Like the Teke, other people in the Congo Basin wore neck rings or collars. Bobangi women, for example, wore copper and brass neck rings weighing over twenty pounds.Copper and brass neck rings were also reported among the Lusakani, the Ntumba, the Luba, the Moie, the Foto, the Ngombe, the Yambuya, and the Lokele. Women and girls, usually the wives, daughters or favorite female slaves of chiefs and other wealthy men, wore neck rings as a way to demonstrate and store their wealth since copper, bronze and brass were, at the time, valuable metals. Writing about his travels in the Congo Basin, English explorer Edward J. Glaves mentions the pride with which the chief of Lukolela, a village on the banks of the Congo river, showed his wife’s “molua” as the large brass neck ring she wore was called. Meanwhile, Bayanzi women were said to place bundles of grass under their heavy brass neck rings to protect their skin. In his record of his travels in the Kingdom of Benguela in present day Angola, English explorer Andrew Battel mentions the practice of women wearing fifteen pound rings of copper about their necks. Among the Fang in nearby Cameroon and Gabon, married women wore pairs of ornately carved copper neck rings which they never removed. As among the peoples of the Congo basin, the ornament served to display the wealth of the man to whom the woman was married. Among the Bamum, also in Cameroon, during official ceremonies, the Tu Panka who is the head of the royal guard and chief warrior of the kingdom, wears a distinctive costume which includes a stiff beaded neck ring and an elaborate headdress made from the feathers of the rare white-crested turaco. Bamun kings also gifted their nobles with brass or copper neck collars depicting the heads of humans and animals. When they died, Bamun kings were buried with several prestige items including brass collars called mbagmbas.

Excavations of burial sites on the island of Mandji (also known as Corisco), located between Equatorial Guinea and Gabon revealed collars made from iron were common burial items while collars made of iron inlaid ivory occur only in one suggesting these were emblems of status. Similarly, excavations of the Sanga burial site on the northern coast of Lake Kisale in the Democratic Republic of Congo revealed collars, rings, bracelets, and beads made of spiralled or woven wire. Among the Yoruba in Nigeria, heavy brass neck collars were used in as adornments in weddings and dances. Meanwhile English anthropologist Percy Amaury Talbot noted among the Kalabari, an Ijaw people in eastern Nigeria, that the women of specific families wore highly valued big bronze torques during funerary rites. So valued were these torques that members of other families who wished to wear them were expected to pay for the privilege to do so. After burial ceremonies the torques were collected and preserved in the memorial shrine. As early as the 1500s, women in the Gold Coast were described as laden with collars, bracelets, hoops and chains, either of gold, copper or ivory. The Bari in South Sudan were reported to wear simple hoops of notched or scalloped iron around their necks. Some women among the Hadza hunter-gatherers in Tanzania wore brass spirals around their necks, a practice they are believed to have copied from the nearby Isanzu. Both Hadza men and women were reported to wear copper bands around their necks. Kikuyu and Maasai women also wore coils of iron or brass wire around their necks. This practice persists among Maasai women who, even today, still wear large coils of brass around their necks. These neck rings are given to them by their husbands as a sign of affection. Brass and copper neck rings are also recorded among the Wanyinka and Chaga people. Neck rings made from copper, bronze and brass were also extensively worn among southern African peoples notably the Zulu, the Lovebu, the Sotho, the Venda, the Lemba, the Tsonga and the Nguni. Dutch trader Jan van de Cappelle noted, while in Maputo Bay (formerly Delagoa Bay), Mozambique, that the people of Chief Mashakatsi i.e., the Venda, bought good quality copper which they smelted with tin into neck and arm rings. Sotho elite wore neck rings called letjekoana, produced by indigenous brass and copper smiths. Meanwhile, the Pedi produced stiff, wide neck rings with triangular designs of beads which indicated rank.

Ornamentation remains a form of non-verbal symbolic communication and a means to store and trade wealth across the African continent. However, under the influence of Christianity, Islam, globalization and other cultural and economic forces, norms around dress, communication, trade currencies and wealth storage mechanisms have changed. This has deeply impacted the prominence of neck ring use both as a prestige ornament and as a signifier or store of wealth even though many peoples retained aspects of their traditional ornamentation, and neck rings still feature prominently in ceremonial garb of some peoples. In the many instances in which neck rings were worn by women and used to indicate their marital status and the relative wealth of their husbands, finger rings now serve this purpose especially in Christianised parts of the continent. In other instances, such as among the Zulu, where neck rings were indicators of status and royal favor, significantly transformed traditional leadership have impacted their use. Furthermore, associated health risks almost certainly had an impact. It is hard to imagine anyone willingly subjecting their subjects or themselves to injuries as occurred among Zulu nobles under King Shaka’s rule for the prestige alone. Additionally, metal neck rings are often confused with manillas, the semi-circular bands of iron, copper, brass, or bronze which were widely used as a trade currency across the continent. It is also possible that in some parts of the continent, manillas were used as neck rings. It stands to reason then that their utility as a trade currency followed the trajectory of manillas which fell out of use with the introduction of less cumbersome currencies and paper legal tenders (backed by more precious metals like gold) as well as the introduction of taxation systems which disincentivized ostentatious displays of wealth.

Neck ring use has not disappeared completely among African peoples and significant effort is being expended in cultural spaces on the African continent and in the African diaspora to revive traditions and reclaim narratives from the distorting grasp of the external influences such as the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and colonialism, or the restricting embrace of cultural norms. An example of this is the use of neck rings, similar to those worn by Ndebele women by the Dora Milaje of Marvel’s Black Panther. In this case, the neck rings indicate not subservience or loyalty to a husband, but the Dora Milaje’s fierce independence and loyalty to the Wakandan people. Communication and its means, whether verbal or non-verbal remains a dynamic endeavour and ornamentation being an element of fashion is subject to the same cycles as other elements of fashion. We might yet see the return of this accessory to the necks of African peoples.

References

Abbot, W. L. “Descriptive catalogue of the Abbot collection of ethnological objects from Kilim-Njaro, East Africa: collected and presented to the United States National Museum.” (1892): Page 1–50.

Amadi, Levi Onyemuche. “Change from Old Currencies to Modern European Currency in Eastern Nigeria: A Classic Example of Administrative Bungles and their Consequences.” Transafrican Journal of History 15 (1986): Page 18–29.

Battell, Andrew. “The strange adventures of Andrew Battell of Leigh, in Angola and the adjoining regions.” №8. Hakluyt Society (1901): Page 18

Bisson, Michael S. “Copper currency in central Africa: the archaeological evidence.” World Archaeology 6.3 (1975): Page 276–292.

Bleek, D. F. “The Hadzapi or Watindega of Tanganyika Territory.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, vol. 4, no. 3, [Cambridge University Press, International African Institute] (1931): Page 273–86, https://doi.org/10.2307/1155255.

Fomine, Forka Leypey Mathew. “A Concise Historical Survey of the Bamum Dynasty and the Influence of Islam in Foumban, Cameroon, 1390–Present.” African Anthropologist 16.1&2 (2009): Page 69–92.

Geary, Christraud M. “Messages and Meaning of African Court Arts: Warrior Figures from the Bamum Kingdom.” Art Journal 47.2 (1988): Page 103–113.

Geary, Christraud. “Bamum thrones and stools.” African Arts 14.4 (1981): Page 32–88.

Glave, Edward James. “In Savage Africa: Or, Six Years of Adventure in Congo-Land”. RH Russell & son, 1892. Page 62

González-Ruibal, Alfredo, Manuel Sánchez-Elipe, and Carlos Otero-Vilariño. “An ancient and common tradition: funerary rituals and society in Equatorial Guinea (first–twelfth centuries AD).” African Archaeological Review 30.2 (2013): Page 115–143.

Guyer, Jane I. “Wealth in people and self-realization in Equatorial Africa.” Man (1993): Page 243–265.

Herbert, Eugenia W. “Aspects of the use of copper in pre-colonial West Africa.” The Journal of African History 14.2 (1973): Page 179–194.

Herbert, Eugenia W.. Red Gold of Africa: Copper in Precolonial History and Culture. United Kingdom, University of Wisconsin Press, 1984. Page 97

Jones, DL. “Towards a Developmental Approach: South African Beadwork.” Newsletter (Museum Ethnographers Group) 9 (1980): Page 2–7.

Marlowe, Frank. “Why the Hadza are still hunter-gatherers.” Ethnicity, huntergatherers, and the ‘Other,’ ed. S. Kent (2002): Page 247–81.

Ratzel, Friedrich. The History of Mankind. United Kingdom, Macmillan, and Company, Limited, 1896. Page 68

Starr, Frederick. Congo natives: an ethnographic album. author, 1912. Page 14, 19, 23, 25, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36

Talbot, Percy Amaury. Tribes of the Niger Delta: their religions and customs. №34. Sheldon Press, 1932. Page 301

Tate, Harry R. “Notes on the Kikuyu and Kamba Tribes of British East Africa.” The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 34 (1904): Page 130–148.

Walker, Ellen Jeanine. “Iron age decorative metalwork in southern Africa: an archival study.” (2016).

Yoon, David. “All That Glitters Is Not Gold: Copper and Value in Precolonial Africa.”

Zaslavsky, Claudia. Africa Counts: Number and Pattern in African Cultures. United States, Chicago Review Press, 1999.